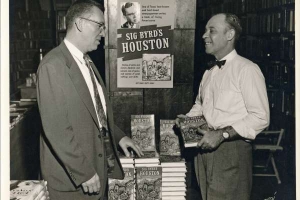

Perhaps it’s fitting that the man’s grave has thus far proven impossible to find — Sig Byrd, the Houston novelist who also happened to be the finest pure writer this city’s journalism industry has ever known — is now unjustly obscure in many other ways. All that can be said with certainty is that Byrd’s funeral occurred on the grounds of Aldine’s Morales Cemetery on a cool December day in 1987 and that his burial there fulfilled a long-held wish.

Byrd’s writing career peaked relatively early, back in the late 1940s and early ‘50s. That was when his bosses at the old daily Houston Press assigned him to write about the city’s underdogs — its half-mad garage inventors, retired sea salts cast away at the Port of Houston never to sail again, and quite often, the denizens of old Houston’s seedy tenderloin, the prostitutes, drug addicts, and drunks, all of whom had their stories, tales Byrd was singularly able to draw out, most of which then ended up in his Press column, The Stroller, and the best of which were harvested and repackaged in his 1955 book Sig Byrd’s Houston, perhaps the most beautifully-written work of nonfiction this city has produced.

In his New York Times review of Byrd’s book, J. Frank Dobie called Byrd’s human subjects “the drift of life,” and by then they had inherited once-prime, then-fallen, and now, quite often gentrified areas which in his day were then known by colorful names like Vinegar Hill (Washington Avenue just west of downtown), Quality Hill (the 19th Century’s River Oaks, then a slum, and now the environs of Minute Maid Park), Pearl Harbor (a now utterly demolished section of Fifth Ward) and Catfish Reef, today’s parking garage-strewn lower Milam Street. Lower Milam today is a sterile dehumanizing landscape, but in Byrd’s heyday, “the Reef” was a dive bar-lined tenderloin peopled by characters with names like Highpockets, the Reverend Elder Love, Deacon Neal the Gospel Man, Monsoor, Gafftop Powell, Sweetie Nelms, and Fenderbender White. Bichon’s Drug Store did a roaring trade in black devil and Louisiana occult candles, dragon-blood sticks, Adam and Eve root, mad water and High John the Conqueror root, for those ailments and occasions for which Western medicine simply would not do.

In his New York Times review of Byrd’s book, J. Frank Dobie called Byrd’s human subjects “the drift of life,” and by then they had inherited once-prime, then-fallen, and now, quite often gentrified areas which in his day were then known by colorful names like Vinegar Hill (Washington Avenue just west of downtown), Quality Hill (the 19th Century’s River Oaks, then a slum, and now the environs of Minute Maid Park), Pearl Harbor (a now utterly demolished section of Fifth Ward) and Catfish Reef, today’s parking garage-strewn lower Milam Street. Lower Milam today is a sterile dehumanizing landscape, but in Byrd’s heyday, “the Reef” was a dive bar-lined tenderloin peopled by characters with names like Highpockets, the Reverend Elder Love, Deacon Neal the Gospel Man, Monsoor, Gafftop Powell, Sweetie Nelms, and Fenderbender White. Bichon’s Drug Store did a roaring trade in black devil and Louisiana occult candles, dragon-blood sticks, Adam and Eve root, mad water and High John the Conqueror root, for those ailments and occasions for which Western medicine simply would not do.

Catfish Reef brought in the best in Byrd’s writing, the jazzy crime noir saxophone, fifth of IW Hopper in the desk drawer, wafts of filterless Pall Mall smoke rising in the humid air prose of a master. As he wrote in Sig Byrd’s Houston, his half-century-out-of-print masterpiece of novelistic non-fiction:

“You can buy practically anything here. Whiskey, gin. wine, beer, a one hundred and fifty dollar suit, firearms, a four bit flop, a diamond bracelet that will look equally good on the arm of a chaste woman or a fun-gal. You can buy fried catfish in Catfish Reef. You can buy reefers on the Reef.

Or you can, get faded, get your picture made, your shoes shined, your hair cut, your teeth pulled. You can get your teeth knocked out for free. You can buy lewd pictures, and in the honkytonks you can arrange for the real thing. The reef is a quietly cruel street, where rents are high and laughter comes easy, where violence flares quickly and briefly in the neon twilight, and if a dream ever comes true it’s apt to be a nightmare.”

Byrd was not an easy man to get along with. He exasperated both bosses and co-workers alike with his brusque manner and maddening eccentricities. While today he has a dedicated cult following, and his name lives on in hip Houston record shop Sig’s Lagoon, one of the few contemporary writers who had only praise for Byrd was his sometimes colleague, sometimes rival Leon Hale. “He was able to do this Damon Runyon stuff about the underworld. Nobody else has been able to do it,” Hale told David Theis in 1994. “He wasn’t afraid to go to 75th Street at 11 p.m. and sit and drink in a sleazy bar and get those stories.”

And it was in the area of 75th Street where he got the story that led to his eventual burial in Aldine’s Morales Cemetery. One day cemetery owner, trailblazing Mexican-American businessman and community leader, and Byrd’s good friend Felix Morales flagged him down, saying he had what just might be a potential story for Byrd. Morales knew and understood Byrd, that the writer could take a sad but then-all-too-common occurrence — the death of a premature infant born to an unwed teenaged mother — and make it into something lasting, forever memorable and touching. And that is just what Byrd did, in a chapter called Segundo Barrio in his book.

Then as now, the Morales Funeral Home was on Canal Street, and it was there that Morales drafted Byrd to drive his nine-passenger Packard up to his cemetery in Aldine. Riding shotgun was Morales’s wife Angie, the first woman in Harris County to earn a mortician’s license. In the back were the bereaved: teenaged Lola, sister of the dead child’s mother Concha, who did not attend the funeral; and Isidro, Lola and Concha’s cousin, who scraped together his last $20 to pay for the funeral. “I don’t know that kind of funeral you can get elsewhere for twenty dollars,” Byrd wrote, “but Felix Morales is kind of an easy touch.”

Also aboard: a tiny casket bearing the mortal remains of Benicia, last name forever unknown, for, as Isidro told Byrd: “We do not know who he is. She will not tell. She says if he doesn’t love her enough to marry her, she will not speak his name.” (Concha and Lola were orphans, Byrd wrote. Lola and Isidro told Byrd that she was a very good girl, “but she is also very pretty, and it is hard for a pretty girl who is poor to be good.”)

All this was told over the sounds of Mexican hits of the day coming out of radio station KLVL, owned by Morales and the first Spanish-language radio station in Houston. Up Hardy they went until they came to Buschong Road, “which,” wrote Byrd, “the locals have informally renamed Morales Road.” There they stopped in a pasture and fed carrots brought along for that purpose to Pete and Dan, Morales’s horses. As they pulled into Morales Cemetery, they were met by a pack of friendly, hungry dogs led by two belonging to Morales, Jack and Teddy, “who knew that the big brown Packard meant a handout.”

And the burial got underway. “The little casket was light as a jewelcase,” Byrd recalled. “As I carried it down a row of mounded graves I couldn’t help thinking how merciful it was that little Benicia had died full of purity and innocence, for had she lived her life would surely have offered many an occasion of evil, in a world of poverty and tears.

We stood around the little grave. Mrs Morales placed the casket on the lowering device and the frail body that been born in sin and was so briefly a living temple of holiness descended into the prairie soil. Mrs. Morales said a prayer in Spanish, we all made the sign of the cross, and Julio [the gravedigger] went to work.”

Escaping from the hot sun, the funeral party adjourned to the cool living room inside the Morales’s ranch house, where their aged maid Lupita brought them cold beer, warm tortillas and soft butter. They spoke of Benicia now more, instead choosing to listen the 80-year-old Lupita chattering on about her new pedalpushers and her life back in Michoacan. Mrs. Morales clicked on the radio, and the room was soon filled with the seductive tones of Maria del Carmen Aleman, “glamorous girl disk jockey” and recipient of 1000 pieces of fan mail each week. Mrs. Morales phone in a couple of requests, and Maria del Carmen obliged, playing “Adios Muchacho” for Don Segismundo (as Sig Byrd was known in Aldine and Segundo Barrio) and “La Burrita” for Lupita, who even at her advanced age loved to ride Pete the horse.

“I’ll never forget little Benicia,” Byrd wrote. “Hers was about the happiest funeral I ever attended.”

Byrd never did forget little Benicia, and his lifelong wish to be buried by Felix Morales was fulfilled, but only just, as Morales passed away about a year later. Finding the site of Byrd’s grave — if it is marked at all — has proved frustrating. It’s not on Findagrave.com, and an emailed query to Morales / Santa Teresa Cemetery (as it is now known) proved fruitless, as did a foot patrol of the 10-acre cemetery on a hot September day. (With no cool living room full of cheerful abuelas, sultry disc jockeys, cold beer and warm buttered tortillas in the offing, perhaps I could be excused for maybe cutting the search a little short. And in case you were wondering, I didn’t see the grave marker for little Benicia, either, but many of the graves were covered with grass clippings from a recent mowing.)

And maddeningly, Byrd’s book remains out of print. Those of us who are proud members of his cult know it won’t remain so forever; we believe the sage Leon Hale, who a quarter-century ago said “A century from now it will sell, as Houston folk history, but not now.”

In the meantime, as we approach Dia de los Muertos, one way to remember this temporarily forgotten writer and his friendship with the Morales family is to commune with his ghost at Morales / Santa Teresa Cemetery. Who knows? Maybe you will find his grave, and maybe even little Benicia’s too.