As with so many fast-growing cities in the 1950s south, Greater Houston and especially Aldine saw much of its population growth coming from country folk moving in from the backwoods, seeking better job and educational opportunities and a little more excitement. For teenagers in the early 1950s, a good deal of those thrills came from breakthroughs in popular music — namely, that fusion of country and R&B that soon enough came to be known as rock and roll, a genre that has spawned hundreds of variants over the last seventy or so years, each with its own signature sound and legions of devotees.

Among the earliest offshoots was rockabilly, that swinging, stripped-down and spare, twangy hollow-body guitar and upright slap bass variant that leans a little closer to country than R&B. Think Elvis Presley hits like “Heartbreak Hotel,” or Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes,” or Johnny Cash’s “Hey Porter”: all are quintessential rockabilly.

Among the earliest offshoots was rockabilly, that swinging, stripped-down and spare, twangy hollow-body guitar and upright slap bass variant that leans a little closer to country than R&B. Think Elvis Presley hits like “Heartbreak Hotel,” or Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes,” or Johnny Cash’s “Hey Porter”: all are quintessential rockabilly.

The style has come in and out of fashion over the years — back in the early ‘80s, bands like the Stray Cats pushed it into full-on craze / revival status. Even today, every big city has a dedicated set of young leather-clad and pomaded hepcat daddios and real gone Bettys who look and talk the part and listen to rockabilly and little else.

And East Aldine’s Brookside Memorial Park is home to the grave of one of the true greats of the genre: the mysterious, mercurial, and revered legend Therman “Sonny” Fisher, a pioneer of the style who lived to reap the benefits of rockabilly’s revival, only to step out of the spotlight both times.

Born into a farming family in the depths of the Great Depression (1930) in Chandler, just outside of Tyler, Fisher spent his childhood following the harvests out west with his family: picking cotton in California and apples in Washington, which is where he was when Texas called him home circa 1950.

Fisher’s dad was a musical man, known to sing cowboy songs to the accompaniment of his own guitar and huddle around the radio to the sounds of Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry with his son before they headed west — Sonny had vowed to one day be up on that stage and heard all around the world, got a guitar, and started practicing, even before he moved to Houston and started a country band.

And on Sonny’s return, there was a new sound coming down across all those many miles of piney woods and cottonfields from Tennessee: rock and roll and rockabilly out of Sun Records of Memphis. Young Fisher was electrified, and made sure he was in attendance when Elvis Presley played his first local shows at places like Cook’s Hoedown Club, the Paladium Club, and Magnolia Gardens. Meanwhile, Fisher was experimenting with his sound, edging away from country while serving as the house band at a northeast Houston (possibly Aldine) beer joint called Dude’s Place. It was there that Fisher met another eventually-legendary Gulf Coast musician — the Spanish Cajun lead guitarist Joey Long. Fisher persuaded Long to saddle up and ride with him and thus was born Fisher’s rockabilly band: the Rocking Boys. (The end of the decade found Long in Louisiana’s Angola prison on a drug charge. There he met two fellow cons by the name of Baldemar Huerta and Mac Rebbenack. On their release, they formed a trio and played on Bourbon Street. Huerta would go on to become Freddy Fender, Rebbenack became Dr. John, and Joey Long wound up in Houston, an elder statesman of the city’s rock and blues scene, a key influence on Johnny Winter, and long the bandleader at the Cedar Lounge on Airline Drive.)

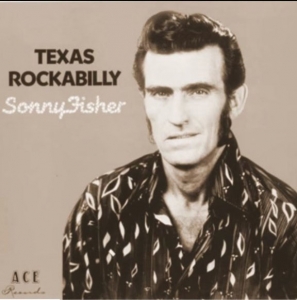

By that time the perpetually rawboned Fisher had developed the slightly sinister image he maintained for the rest of his days: jet-black hair in a tall pompadour over a high-cheekboned face lined by long sideburns trimmed with precision at his chiseled jawline. Basically a scarier Joaquin Phoenix as Johnny Cash or the Hollywood ideal of a rockabilly superstar.

And for a while there it looked like he just might give Elvis, Johnny, Gene Vincent, and Carl Perkins a run for their money. His big break came at a Houston club called the Cosy Corner, where he was spotted by Jack Starnes, manager of country star Lefty Frizzell and co-owner of Houston’s Starday Record label, future home of George Jones, the Big Bopper, Roger Miller and Willie Nelson, among others. Starnes signed Fisher to a deal and Fisher cut eight songs, including singles like “Rockin’ Daddy,” “Pink and Black,” and “Hey Mama,” were solid hits in Texas and the South. At 24 years old, the future looked very bright for Sonny Fisher, but he fell victim to a combination of music industry sleaze and his own pride: at the end of the year, Starday handed him a check for a measly $126 for his share of the royalties for all his songs.

Harsh words were exchanged and Fisher and Starday parted ways. Fisher attempted to run his own record label — such artist-run enterprises were years away from success, and Fisher’s Columbus label was no exception. In 1958, he attempted a very bold move — he fronted an R&B band in which he was the only white member, but seven years before the full institution of Civil Rights, this was too much too soon. Discouraged, Fisher quit the business and spent the next few years laying floors in and around northeast Houston and Aldine.

And that would have been that were it not for the rockabilly craze of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. For some kids at that time, mainstream rock had become overbearingly bombastic and pretentious — think bands like Yes, the Moody Blues, King Crimson, and Pink Floyd. Stripped-down punk was one response to all that excess; another was a revived interest in rockabilly, many of whose pioneers were still living and in good fighting form — few more so than Sonny Fisher. In search of getting permission to license Fisher’s 1950s recordings, Ted Carroll of London’s Ace Records, tracked Fisher down in Crosby, where by then he’d taken work in a sawmill. Fifteen years ago, Carroll recalled that Fisher was stunned to learn that he’d made a name for himself all those years ago half a world away.

“He was a humble, courteous man,” Caroll told London’s Guardian newspaper in 2005, shortly after Fisher passed away. “When we brought him to Britain he still looked great – big pompadour, long sideburns, really slim, a stunning looking man – so the kids loved him. We recorded a new EP with him. He then got very popular in France and made recordings there.”

And for reasons he never explained, Fisher chose not to follow up on that success as much as many others might have. Time after time, he turned down offers from European promoters for tours and from label heads for studio sessions. He did make one exception: in 1993, he cut a record and toured Spain, backed by and alongside the recently deceased Sleepy LaBeef, like Fisher, a staple of east Houston’s rockabilly scene in the 1950s. And that was that — he died of unknown causes and was buried in Brookside in October of 2005.

Live 1980s performance of “Rockin’ Daddy”