In recognition of Black History Month, students in the Aldine Independent School District are competing in a speech contest on the theme of this year’s celebrations: Resilience.

In recognition of Black History Month, students in the Aldine Independent School District are competing in a speech contest on the theme of this year’s celebrations: Resilience.

But today’s students will be hard-pressed to top a 1988 essay written by Erika Sampson, who was an Aldine-Eisenhower senior then. Her essay was reprinted in March 1990 in the Texas Historian, a publication of the Texas State Historical Association.

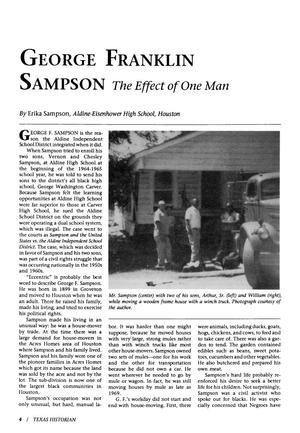

In “The Effect of One Man,” Sampson tells the story of her “eccentric” and modest grandfather George Franklin Sampson. A house mover by trade, he wanted his two sons to attend Aldine High School. When he was told the boys would have to attend the all-Black Carver High School, Sampson filed a federal civil rights lawsuit.

Born in Groveton in 1899, Sampson became one of the early settlers in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Acres Homes. He never owned a car or truck; he used two gray mules and a winch trailer to move houses in northeast Harris County.

His granddaughter, citing history books and family sources, wrote in her essay that – in addition to the mules – Sampson also kept ducks, goats, hogs, chickens and cows at the family homestead. He raised his family, along with a variety of vegetables in a large garden, as he sowed the seeds of activism for civil rights causes.

Because of Sampson’s lawsuit, U.S. District Judge Joe Ingraham required Aldine ISD to integrate its schools. The decision, in 1965, was more than a decade after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark desegregation decision in Brown vs. Board of Education.

By the time the lawsuit was settled, Sampson’s sons, Vernon and Chesley, were too old to attend Aldine schools. But his family’s struggle for civil rights continued. He died in 1983. The Sampson family left his funeral and went together to cast their votes in a local election.

Erika Sampson wrote: “In the 1950s and 1960s, blacks struggled for equality and their civil rights. The fight was slow, hard and very painful, (because) racism and discrimination were rampant throughout the nation, especially in the South. Assassinations, fighting and killings were signs of the time.”

Sampson went on to graduate from the University of Houston, She later worked as a nutritionist for the Aldine, Cy-Fair, and Prairie View independent school districts.

Sampson went on to graduate from the University of Houston, She later worked as a nutritionist for the Aldine, Cy-Fair, and Prairie View independent school districts.

Aldine ISD remained under a federal court order until 2002 and the school system quickly became a nationally recognized leader in equal educational opportunity. In 2009, Aldine ISD was awarded the Broad Prize, a $1 million award given to public schools that have demonstrated the greatest overall improvement in student achievement among low-income or minority students.

Aldine ISD Superintendent Dr. LaTonya Goffney recently explained the district’s choice of “Resilience” as the theme of the district’s celebration of Black History Month:

“Resilience recognizes the power of the Black community to withstand and overcome the systemic oppression and discrimination they have faced throughout history, while also honoring the strength, determination and perseverance of Black individuals and communities to survive, thrive and make positive contributions to society.”

Goffney is, herself, a model of resilience. She is president-elect of the National Association of Black School Educators as well as president of the Texas Association of School Administrators.

The district is holding weekly events each Friday in February to celebrate black history.

Campus competitions in the oral presentation contest started on Jan. 23 and continue through Feb. 17. The district competition will take place Feb. 20-22.

In the meantime, the BakerRipley non-profit’s East Aldine Town Center campus, 3000 Aldine Mail Route Rd., will host a Black History Month celebration 5-7 p.m. on Feb. 17. The outdoor event will include music, food trucks, craft activities, dance performances and prize drawings. Participants are encouraged to call 346-570-4463 in advance.

— By Anne Marie Kilday–