Participatory democracy can be an emotional affair, and few aspects of it elicit quite as much primal passion as the education of our children. Aldine is no exception, and about 60 years ago, its tempestuous school board meetings made national news, and in its resolution, Aldine ISD found a hero in W.W. Thorne whose name still rings out in the area.

Participatory democracy can be an emotional affair, and few aspects of it elicit quite as much primal passion as the education of our children. Aldine is no exception, and about 60 years ago, its tempestuous school board meetings made national news, and in its resolution, Aldine ISD found a hero in W.W. Thorne whose name still rings out in the area.

As with the rest of greater Houston, the 1950s found Aldine growing faster than its citizens’ ability to cope. More young families moving in meant more schools needed to go up, and as soon as one opened its doors, it filled to capacity, requiring more funds to build another, and another, and so on.

This required a steady rise in property taxes, and as ever, that didn’t sit well with everybody, and some of the anti-tax crowd found their way onto the school board and set taxes at a rate low enough to inevitably cause a budget shortfall.

The looming crisis first became apparent in the summer preceding the 1958-59 school year, and that was when the first skirmishes of the Great Aldine School Board War were fought.

The Boston Massacre of the conflict came on June 17 when citizen Ray Maxwell slapped Aldine School Board president Robert L. Whitmarsh across the face after a tempestuous meeting. “I don’t like the way they are running our schools,” Maxwell told reporters. Hauled into justice of the peace court on a charge of “creating an incident,” the Crispus Attucks of this revolution, was fined $1 plus court costs of $22.50.

Battle was truly joined in July 1958 when the Aldine School Board refused to recognize a taxpayer petition demanding the resignation of four its members.

“The fight involved more than a dozen persons, including board member Carl R. Tautenhahn, one of those named in the petition,” reported United Press International. “Witnesses say the melee started when Tautenhahn shoved W.P. Stokely after engaging in a heated word exchange with several persons. Stokely hit Tautenhahn in the face and was immediately struck by B.B. Cathey, a school employee. Someone else struck Cathey and the scene turned into a pile of struggling bodies. Several persons involved were trying to disentangle others. One man had a chair wrenched from his hands.”

“The fight involved more than a dozen persons, including board member Carl R. Tautenhahn, one of those named in the petition,” reported United Press International. “Witnesses say the melee started when Tautenhahn shoved W.P. Stokely after engaging in a heated word exchange with several persons. Stokely hit Tautenhahn in the face and was immediately struck by B.B. Cathey, a school employee. Someone else struck Cathey and the scene turned into a pile of struggling bodies. Several persons involved were trying to disentangle others. One man had a chair wrenched from his hands.”

As another short Houston spring began warming into summer, Aldine’s schools lacked the money to make payroll for teachers and staff. Schools closed after a walkout in mid-April dragged on towards May. Some students temporarily enrolled in Houston schools, which accepted them for a fee of about $20; others got a jump on the summer holidays.

Meanwhile tensions between their parents and the rival factions on the school board continued to mount and finally erupted on April 30 in the high school auditorium, where a meeting had been convened by request of board members Tautenhahn, Whitmarsh, and their ally on the board, Harry Ammons.

This group said they had a plan to pay the teachers and reopen the schools, but after the meeting was convened, Whitmarsh told the 1000-strong crowd that it would only be enacted after two new members joined their ranks on the board a few days later.

According to the Associated Press, that prompted an “angry roar” from the crowd. Board president Richard Cass replied that the entire board should resign thus offering Aldine a chance to start with a clean slate. Cass had a majority of the seven-man board on his side, albeit with one man voting in absentia from Alaska, which gave the Whitmarsh faction wiggle room. They refused to resign, with Whitmarsh demanding to know how the three men present in the room could present themselves as a majority.

When a motion to adjourn was presented with the fate of the district still in limbo, a group of parents rushed the stage and something akin to a royal rumble / battle royale broke out.

“George Whitmarsh, a brother of the board member, jumped on the stage with a chair. He was seized and pulled from the stage. Ammons also was shoved from the stage. Robert Whitmarsh engaged in a duel of chairs with several people.”

Harris County deputies prudently called in beforehand extracted the bloodied and bruised Whitmarsh and Ammons from the crowd and whisked them away to a restroom, where Ta utenhahn had already found asylum. George Whitmarsh emerged from the fray with a tremendous goose-egg on one eye. “I have been hit hard in my time but that was the hardest ever,” he told a reporter. “Somebody struck me with a chair.”

utenhahn had already found asylum. George Whitmarsh emerged from the fray with a tremendous goose-egg on one eye. “I have been hit hard in my time but that was the hardest ever,” he told a reporter. “Somebody struck me with a chair.”

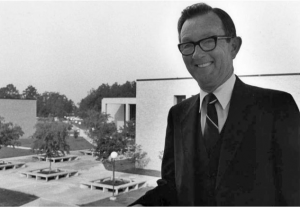

That battle had ended but the war dragged on, albeit now one of words instead of fists and chairs. On the night of May 5, 750 people gathered in the auditorium for a 7:30 meeting which appeared ready to commence right on time. With no explanation, all seven board members left the stage at the stroke of half past seven, leaving the crowd to mutter amongst themselves for 20 minutes until new superintendent W.W. Thorne told the crowd that the meeting would be delayed a further 45 minutes. Thorne offered no explanation and walked backstage.

And the crowd waited, and waited, and waited. Some 125 of them finally left. At last, the meeting was called to order amid high drama at ten minutes until ten. The school’s PA crackled with the voice of Cass, the board’s president, who announced that Whitmarsh had threatened to personally kill him if the crowd turned against him as it had at the previous meeting. Cass said that he had spent the day attempting first to file charges against Whitmarsh, and when talked out of that by a justice of the peace, arranging a police escort to accompany him to the meeting.

By this time, Whitmarsh, Tautenhahn and Ammons had left the meeting to attend a house party, but not before sending word that they, too, had sought police protection that day. Harris County chief deputy Loyd Frazier agreed to send men to the premises, but balked at having them in the room during the meeting. “We just can’t afford to referee those people’s fight before they start it,” he told reporters. In that he was overruled by a ranking officer, and there were police in the room when the meeting did come to order. Lots and lots of police — some 60 officers from agencies including the sheriff’s office, the Department of Public Safety, and even a few Texas Rangers were reported on the scene or in the vicinity.

Whitmarsh’s faction did not come back to the meeting, and Cass told reporters that Whitmarsh’s claim of a threat against his life was “the silliest thing I ever heard of.” The meeting ended with Cass telling parents that he “had no idea” when the schools would reopen, that he and his allies were doing the best that they could, and that the board minority did not have the best interests of the students in their hearts.

“If I was as big as Cass, I wouldn’t be running around afraid somebody was going to beat me up,” Whitmarsh fired back. Cass claimed he feared not for his personal safety but only wanted to avoid a second school board riot.

And he did, and there were no more violent flare-ups. Meanwhile, to meet payroll, Thorne and a local lawmaker helped to secure an emergency sale of $200,000 worth of time warrants.This lightning maneuver was the fastest the Texas legislature had ever moved on any issue, ever — Thorne reminisced years later that it took all of one day to win approval and the governor’s signature in a single day.

And after some wrangling over who had the standing to sign the checks, the Thorne-Cass faction won out, the board dissolved and was reformed afresh, and schools reopened just in time for summer break.

And after some wrangling over who had the standing to sign the checks, the Thorne-Cass faction won out, the board dissolved and was reformed afresh, and schools reopened just in time for summer break.

Thorne, the then-new superintendent, had worked his way up to that position after starting out as a teacher / bus driver in 1950. In a 2002 interview with the Houston Chronicle, Thorne told a reporter that the situation he walked into was “tough,” one in which “if three of the board members said it was raining, the other four would swear the sun was shining.”

There was an unexpected silver lining in the peace the followed the Great Aldine School Board War of 1959 — a newfound respect for and appreciation of education.

As Thorne told the Chronicle:

“From there on, the situation turned around. A community which had been kind of `leave it to John to tend to’ suddenly became very concerned about their school system. Not many things get the community’s attention more than closing the public schools. So, the community became really involved in the schools and very supportive of better education.”

Thorne’s troubles weren’t over yet. Just a few years later, in 1961, he faced a petition drive aimed at his ouster. Aldine High School was in “turmoil,” read that signed declaration, all because of Thorne and principal C.L. Chandler.

The petition’s author, one Elmer Dover, told reporters that he had hundreds of signatures and that he would be presenting it to the board at some time in the not-too-distant future.

“I presume the turmoil he refers to has something to do with his son being ruled ineligible,” Thorne replied.

“I presume the turmoil he refers to has something to do with his son being ruled ineligible,” Thorne replied.

Dover’s son, you see, was the star quarterback for Aldine High. After a hot start with young Dover under center, the Mustangs had gone into a tailspin, losing three out of the four games, thanks in no small part to Dover’s absence from the squad over that span. And that absence came about because Dover flunked three out of his six classes, which were more than enough to get you the boot from your team even before H. Ross Perot made “no-pass no-play” the law of the land.

What turmoil arose from Dover’s absence from the 1961 Aldine Mustangs football squad abated without bloodshed, and today, each of the Aldine Independent School District’s football teams play their home games in Thorne’s namesake stadium. Scholars 1, Jocks 0.

Thorne served as superintendent until 1972, when he resigned to serve as president of North Harris College until his retirement in 1982. North Harris College — today a component of the Lone Star College system — is another story for another time, but one in which Thorne, the father of modern-day Aldine education, played a key role.