Editor’s Comments:

Below you’ll find the first in a series of (at least) 3 articles focusing on the history of Aldine and some of its earliest settlers. Our writing staff is exploring local activities, folklore, and documented history in an effort, in part, to ensure Aldine’s history is properly celebrated and curated for all to enjoy.

Keep your eyes peeled in both April and May when we run parts 2 and 3.

Aldine History

by EAMD staff

Early Days, and How Did Aldine Come to Get Its Name?

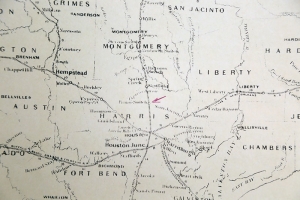

Though there had been scattered farms since the earliest days of Texas, the place we now know as Aldine began life first as a place called “Greens” (or maybe Green’s, as in Green’s Bayou) and then, in 1873, when it became a whistle-stop on the International and Great Northern Railroad, it was renamed Prairie Switch. Trains chugging up from Houston and bound for Palestine, then the railroad’s northern terminus, would switch engines there on that prairie.

Though there had been scattered farms since the earliest days of Texas, the place we now know as Aldine began life first as a place called “Greens” (or maybe Green’s, as in Green’s Bayou) and then, in 1873, when it became a whistle-stop on the International and Great Northern Railroad, it was renamed Prairie Switch. Trains chugging up from Houston and bound for Palestine, then the railroad’s northern terminus, would switch engines there on that prairie.

Both the town and the railway switched names too — after linking up to Dallas and points north, west and east, the International became the Missouri Pacific, and sometime before 1887 Prairie Switch became Aldine. (And this Prairie Switch is not to be confused with that other one that became El Campo, nor is this Aldine to be confused with that other one, the ghost town out near Uvalde that’s just a cemetery now.)

Origin stories for how Aldine got its name are quite numerous. Maybe the most fanciful one is this: when the International’s trains would grind to a halt in Prairie Switch, the conductor, knowing the train would remain still for a while, would holler out “All dine!” to the passengers, signaling to them that they could leave the train and eat inside the station.

That’s just a little too perfect, a little hokey, too cute, and if it were true, it seems like there would be hundreds of Aldines all over America. Engines were switched on any steam trip of any length, and if conductors made this announcement every time, people would be mistaking every other frontier stopping place for a town called All-dine and calling it such.

Other sources cite a mysterious “local family” as the inspiration for the name, but nobody has said who these people were, nor even if this was a first or last name. Aldine is a very rare surname — however, it did enjoy a brief vogue as a girl’s first name in the Victorian age.

Even as little girls were being named Aldine in more numbers than ever before or since, there existed an art/literary magazine born as The Aldine Press, later known simply as The Aldine. It was widely popular at the time Prairie Switch the whistle-stop was being reborn as Aldine the village, and the periodical’s fame seemed to have made the name Aldine very stylish for a time. And not just for little girls — one of the Vanderbilts owned a renowned racehorse by that name, and one of the grandest hotels in Philadelphia was the Aldine. Chicago had an Aldine Square that became briefly infamous for its peripheral role in the Haymarket Riot.

And there was also a now-forgotten town in Kansas, just south of its border with Nebraska, called Aldine. Aldine, Kansas had a blink-and-you’ve-missed-it existence — today a Google search turns up almost nothing, but a deep dive into newspaper databases turns up numerous mentions of goings-on in the Norton County town back in the 1870s and ‘80s.

But back to the magazine.

The publication “The Aldine” as referred to in our piece was notable for its rich imagery and writings, as noted here. The Bastrop Advertiser (Bastrop, Tex.), Vol. 17, No. 19, Ed. 1 Saturday, April 4, 1874 Page: 2 of 4

In the days before cinema and TV, artistic publications like The Aldine were one of the only sources of man-made visual stimulation for rural Americans and thus were far more widely circulated than art magazines today. Billed in 1872 as “an Illustrated Monthly Journal claimed to be the handsomest Paper in the world.”

Often, as lagniappe for subscribers, these magazines would throw in full-color “chromos” — reproductions of popular paintings suitable for framing, and The Aldine was no exception. One year its marketing team dangled a chromo of a now-forgotten work by an unnamed artist (albeit a painting said to be widely renowned in its day) called “Dame Nature’s School” as an incentive to would-be subscribers.

The Aldine frequently featured works of the Hudson River School of art — romanticized landscape paintings of rural Edens, the nature-loving words of writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau brought to life on painted canvas. The Aldine’s literary philosophy ran towards the pastoral as well. According to art historian Janice Simon, The Aldine published many “extensive accounts of what the editors deemed the nation’s most picturesque and sublime regions” in America.

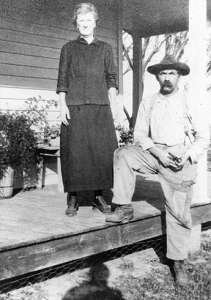

Perhaps that was what Aldine’s first settlers hoped to create there in north Harris County — a little slice of heaven where man and nature and agriculture and modernity coexisted in harmony.

I have no proof to back this theory, but neither do those who speculate that the name derives from a local family. To me, though, The Aldine seems to me a likelier inspiration for the town’s name than some settler with a very rare last name who was also so obscure as to have seemingly appeared from nowhere and then vanished without trace.

And it is also very possible that Aldine, Texas is named after Aldine, Kansas. As we shall see, Jayhawks were quite numerous among the area’s earliest settlers. Maybe it was up there on the Great Plains that a copy of The Aldine inspired a reader to bestow the name upon the surrounding town. Or maybe the Kansas town was named after somebody’s daughter, who in turn was inspired by the magazine.

Maybe so, maybe no, but that brings us to another question — how did the magazine itself come by that name? What does Aldine mean?

Maybe so, maybe no, but that brings us to another question — how did the magazine itself come by that name? What does Aldine mean?

Take it away, Noah Webster: “[a work] printed or published by Aldus Manutius of Venice or his family in the 16th century who produced fine editions of chiefly Greek, Latin, and Italian classics, each book usually bearing an anchor and dolphin emblem.”

So, Aldine derives from Aldus the same way words like Raphaelite and Da Vincian come from Raphael and Da Vinci.

Aldine got its first post office in 1897, servicing about 25 or 30 local families, most of them farmers of Swedish descent. The Scandinavian transplants had planted groves of satsumas and pears and fig orchards and trundled their produce down to sell in Houston’s teeming Market Square, or, if they had enough, packed the excess into crates and shipped it away on the International’s box cars. Documentation of these Swedes is hard to come by, you can find some in an 1898 edition of The Lutheran Companion, which notes that a Reverend A.P. Sanden had moved from Iowa to Aldine to minister to the Swedes both there and in Houston, “which is quite a hard field, as anyone who has had anything to do with church work at that place can testify.” And a “employees wanted” ad in an 1898 edition of the Houston Post sought a “Swede for Farm Work” in Aldine.

Continue with part two.Continue with part two.